“Behind the Lines”

The story of Queensland Soldiers Behind the Lines.

A special digital exhibition for

Anzac Day 2024.

Originally produced with the assistance of the Royal Historical Society of Qld and shown at the Commissariat Store Museum 2018-2019.

Thanks to RHSQ for their support to produce the exhibition.

The story of Queensland Soldiers Behind the Lines.

A special digital exhibition for

Anzac Day 2024.

Originally produced with the assistance of the Royal Historical Society of Qld and shown at the Commissariat Store Museum 2018-2019.

Thanks to RHSQ for their support to produce the exhibition.

| behind_the_lines_brochure_final.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2288 kb |

| File Type: | |

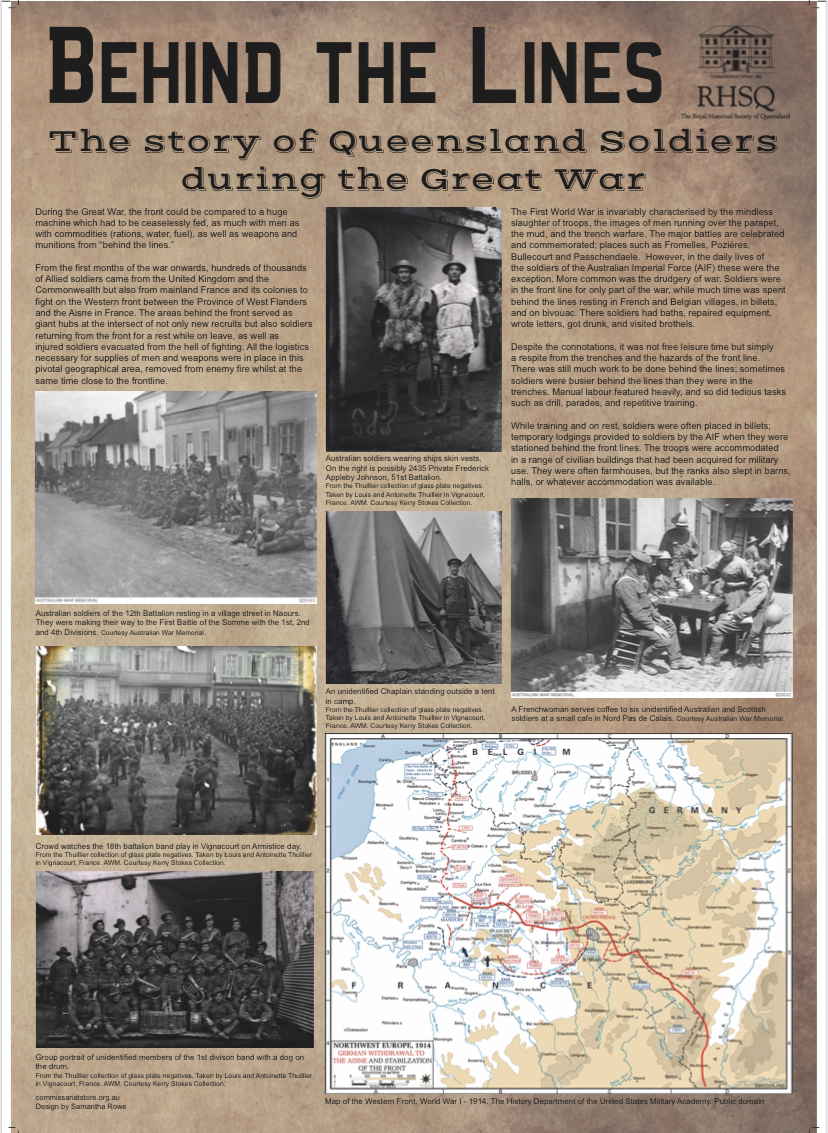

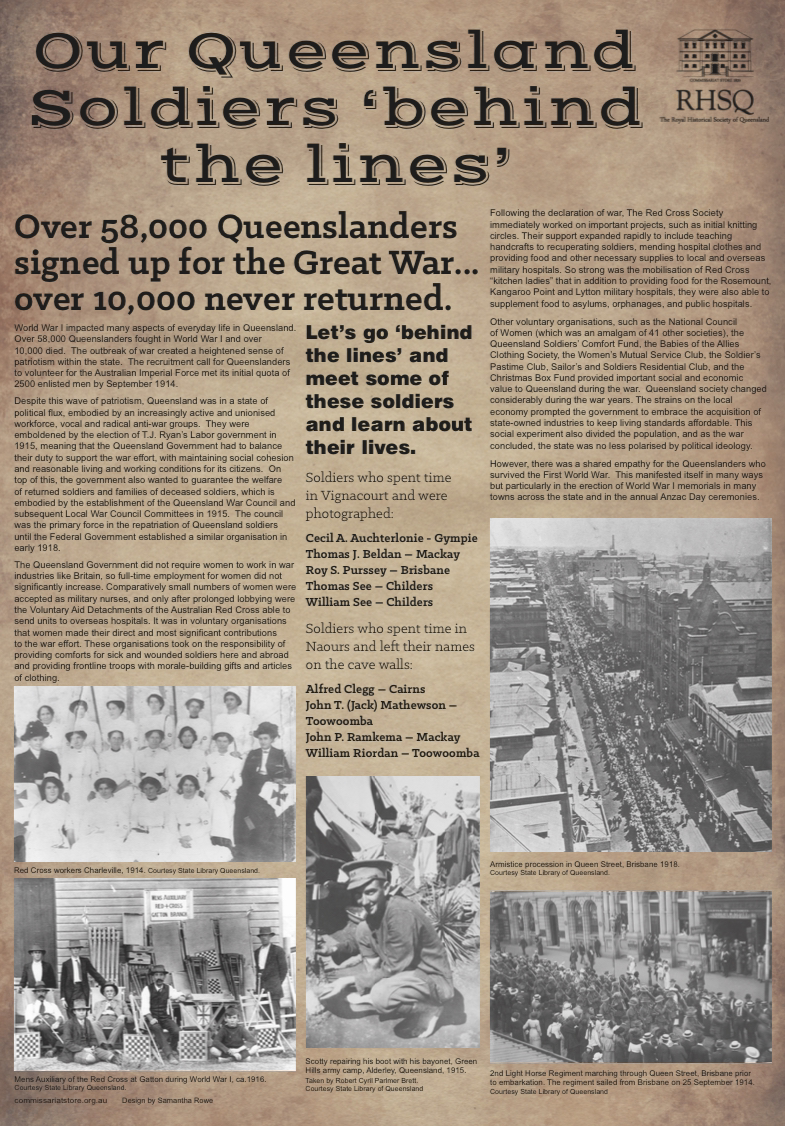

During the Great War, the front could be compared to a huge machine which had to be ceaselessly fed, as much with men as with commodities (rations, water, fuel), as well as weapons and munitions from “behind the lines.”

From the first months of the war onwards, hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers came from the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth but also from mainland France and its colonies to fight on the Western front between the Province of West Flanders and the Aisne in France. The areas behind the front served as giant hubs at the intersect of not only new recruits but also soldiers returning from the front for a rest while on leave, as well as injured soldiers evacuated from the hell of fighting. All the logistics necessary for supplies of men and weapons were in place in this pivotal geographical area, removed from enemy fire whilst at the same time close to the frontline.

The First World War is invariably characterised by the mindless slaughter of troops, the images of men running over the parapet, the mud, and the trench warfare. The major battles are celebrated and commemorated; places such as Fromelles, Pozières, Bullecourt and Passchendaele.

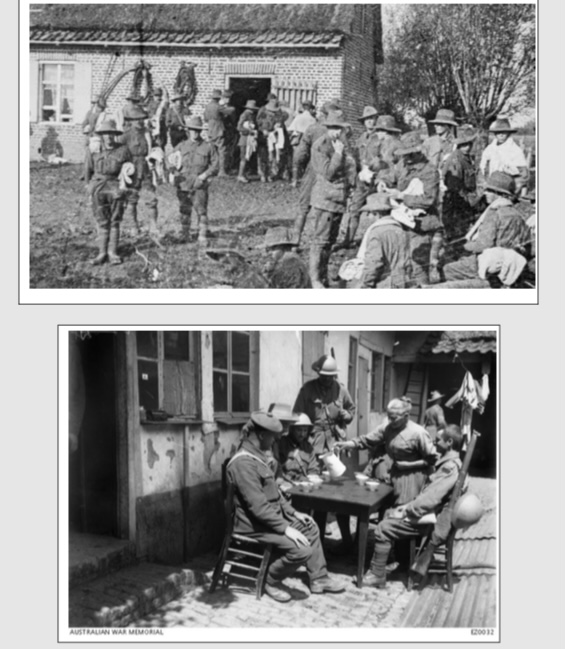

However,in the daily lives of the soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) these were the exception. More common was the drudgery of war. Soldiers were in the front line for only part of the war, while much time was spent behind the lines resting in French and Belgian villages, in billets, and on bivouac.There soldiers had the opportunity to have baths, repair equipment, write letters, get drunk and perhaps visit brothels.

From the first months of the war onwards, hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers came from the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth but also from mainland France and its colonies to fight on the Western front between the Province of West Flanders and the Aisne in France. The areas behind the front served as giant hubs at the intersect of not only new recruits but also soldiers returning from the front for a rest while on leave, as well as injured soldiers evacuated from the hell of fighting. All the logistics necessary for supplies of men and weapons were in place in this pivotal geographical area, removed from enemy fire whilst at the same time close to the frontline.

The First World War is invariably characterised by the mindless slaughter of troops, the images of men running over the parapet, the mud, and the trench warfare. The major battles are celebrated and commemorated; places such as Fromelles, Pozières, Bullecourt and Passchendaele.

However,in the daily lives of the soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) these were the exception. More common was the drudgery of war. Soldiers were in the front line for only part of the war, while much time was spent behind the lines resting in French and Belgian villages, in billets, and on bivouac.There soldiers had the opportunity to have baths, repair equipment, write letters, get drunk and perhaps visit brothels.

Despite the connotations, it was not free leisure time but simply a respite from the trenches and the hazards of the front line.There was still much work to be done behind the lines; sometimes soldiers were busier behind the lines than they were in the trenches. Manual labour featured heavily, and so did tedious tasks such as drill, parades,and repetitive training.

While training and on rest, soldiers were often placed in billets; temporary lodgings provided to soldiers by the AIF when they were stationed behind the front lines. The troops were accommodated in a range of civilian buildings that had been acquired for military use.They were often placed in farmhouses, but the ranks also slept in barns, halls, or whatever accommodation was available.

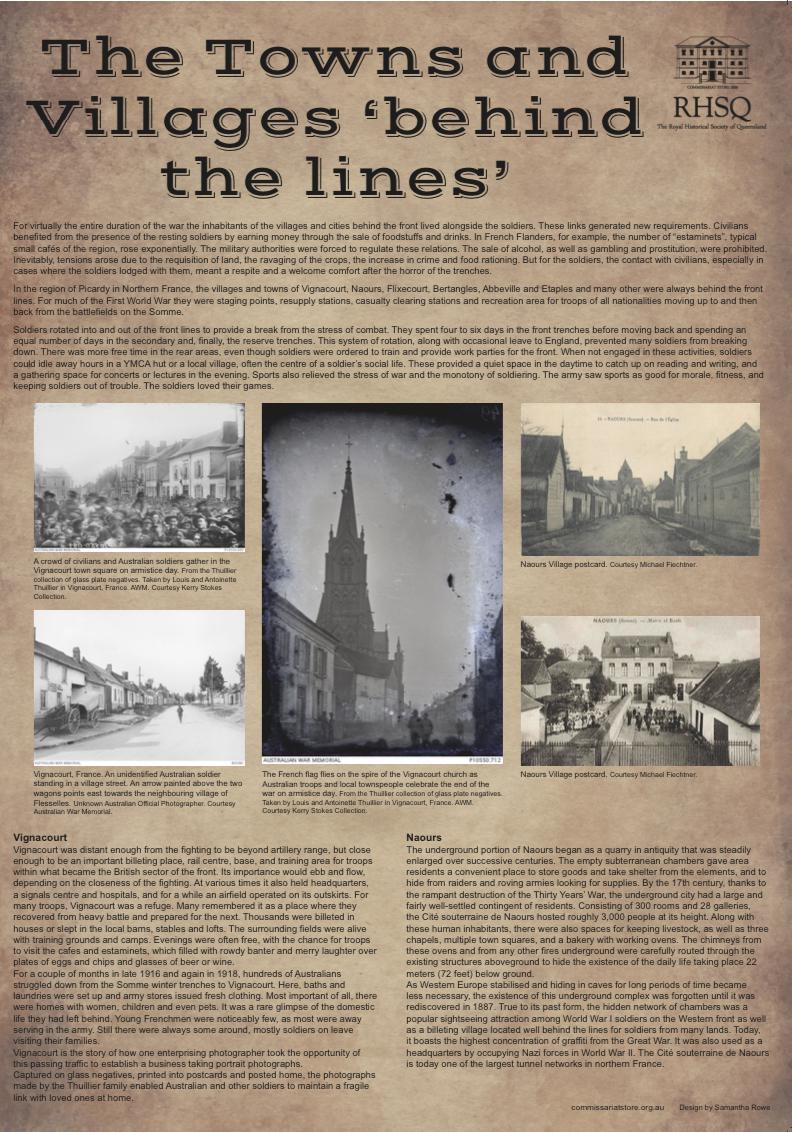

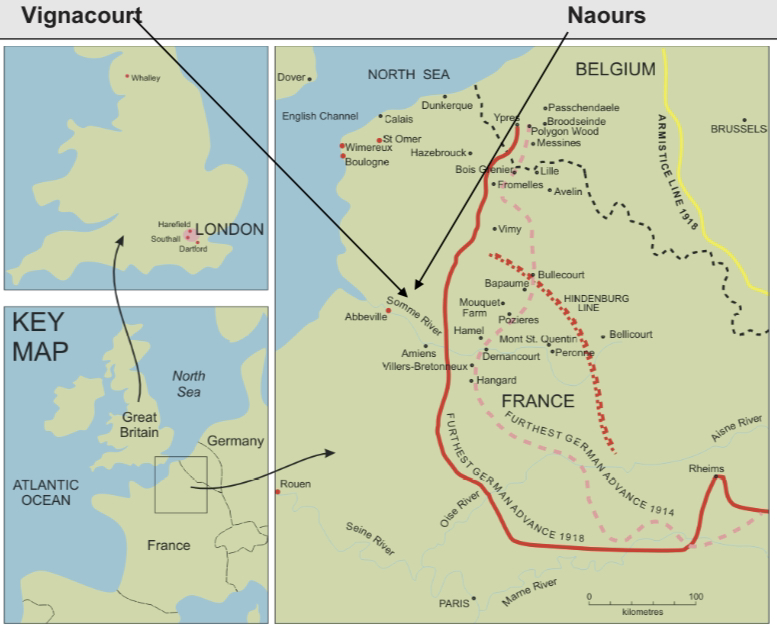

The Towns and Villages “behind the lines”

In Northern France in Picardy,the villages and towns of Vignacourt and Naours, Flixecourt, Bertangles, Abbeville and Etaples and many other were always behind the front lines. For much of the First World War, they were staging points, resupply stations, casualty clearing stations and recreation area for troops of all nationalities moving up to and then back from the battlefields on the Somme.

Soldiers rotated into and out of the front lines to provide a break from the stress of combat. They spent four to six days in the front trenches before moving back and spending an equal number of days in the secondary and finally, the reserve trenches. This system of rotation, along with occasional leave to England, prevented many soldiers from breaking down.

There was more free time in the rear areas, even though soldiers were ordered to train and provide work parties for the front. When not engaged in these activities, soldiers could idle away hours in a YMCA hut for a local village,often the centre of a soldier’s social life. These provided a quiet space in the daytime to catch up on reading and writing, and a gathering space for concerts or lectures in the evening.

Sports also relieved the stress of war and the monotony of soldiering. The army saw sports such as boxing and football as good for morale, fitness, and keeping soldiers out of trouble. The soldiers loved their games.

( selected texts courtesy Life in the Rear- Jessica Bretherton AWM)

In Northern France in Picardy,the villages and towns of Vignacourt and Naours, Flixecourt, Bertangles, Abbeville and Etaples and many other were always behind the front lines. For much of the First World War, they were staging points, resupply stations, casualty clearing stations and recreation area for troops of all nationalities moving up to and then back from the battlefields on the Somme.

Soldiers rotated into and out of the front lines to provide a break from the stress of combat. They spent four to six days in the front trenches before moving back and spending an equal number of days in the secondary and finally, the reserve trenches. This system of rotation, along with occasional leave to England, prevented many soldiers from breaking down.

There was more free time in the rear areas, even though soldiers were ordered to train and provide work parties for the front. When not engaged in these activities, soldiers could idle away hours in a YMCA hut for a local village,often the centre of a soldier’s social life. These provided a quiet space in the daytime to catch up on reading and writing, and a gathering space for concerts or lectures in the evening.

Sports also relieved the stress of war and the monotony of soldiering. The army saw sports such as boxing and football as good for morale, fitness, and keeping soldiers out of trouble. The soldiers loved their games.

( selected texts courtesy Life in the Rear- Jessica Bretherton AWM)

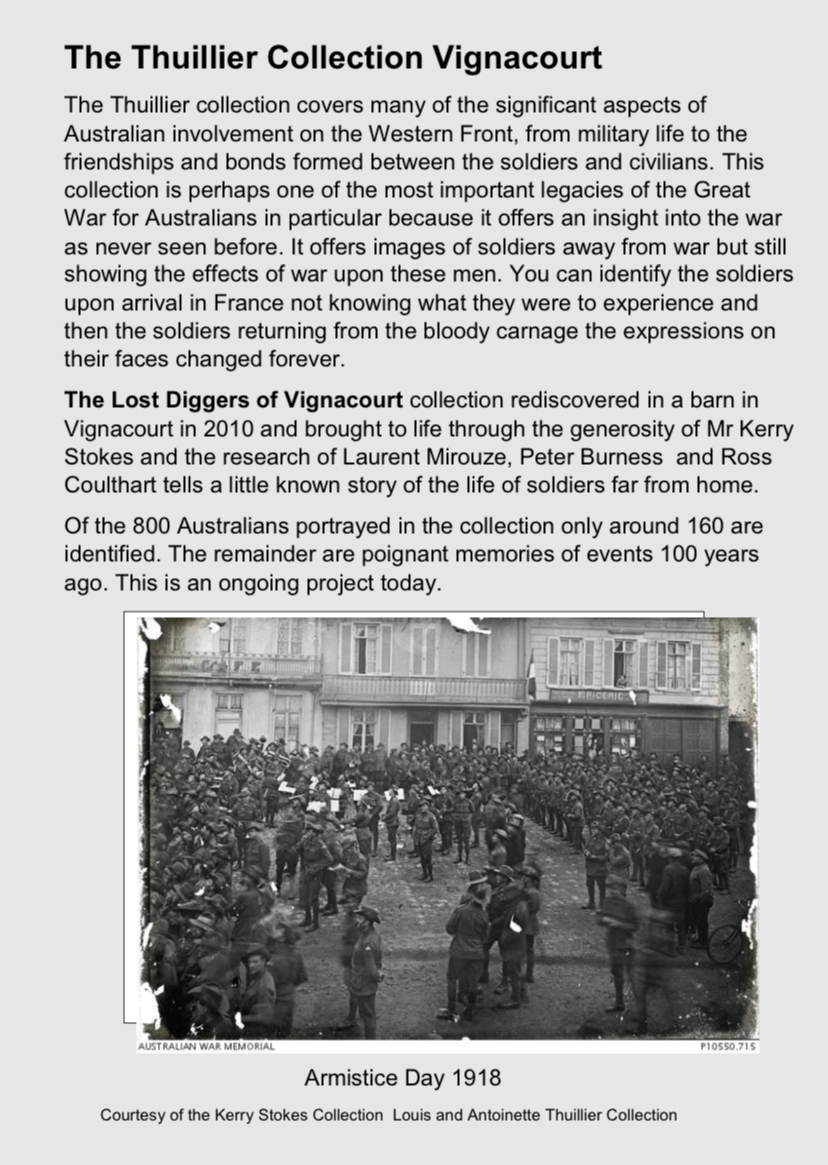

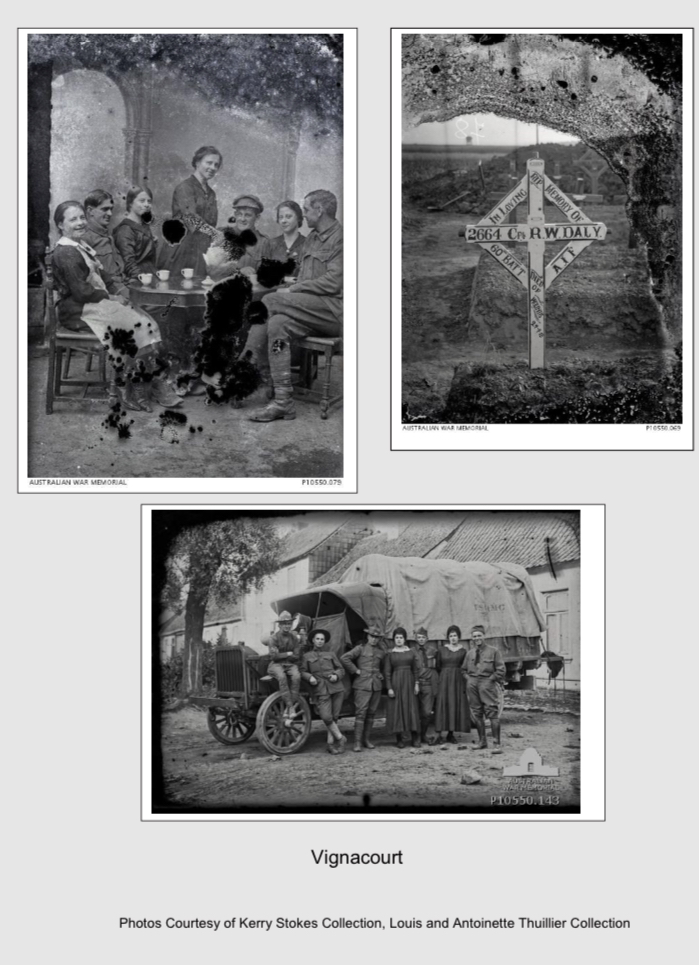

Vignacourt

Vignacourt was distant enough from the fighting to be beyond artillery range but close enough to be an important billeting place,rail centre, base, and training area for troops within what became the British sector of the front. Its importance would ebb and flow, depending on the closeness of the fighting. At various times it also held headquarters, a signals centre and hospitals, and for a while an airfield operated on its outskirts. For many troops Vignacourt was a refuge. Many remembered it as a place where they recovered from heavy battle and prepared for the next. During the war thousands were billeted in houses or slept in the local barns, stables and lofts. The surrounding fields were alive with training grounds and camps. Evenings were often free, with the chance for troops to visit the cafes and estaminets, which filled with rowdy banter and merry laughter over plates of eggs and chips and glasses of beer or wine.

Photo Naours 1916 courtesy AWM

For a couple of months in late 1916 and again in 1918, hundreds of Australians struggled down from the Somme winter trenches to Vignacourt. Here baths and laundries were set up and army stores issued fresh clothing. Most important of all, there were homes with women, children and even pets. It was a rare glimpse of the domestic life they had left behind. Young Frenchmen were noticeably few, as most were away serving in the army. Still there were always some around, mostly soldiers on leave visiting their families.

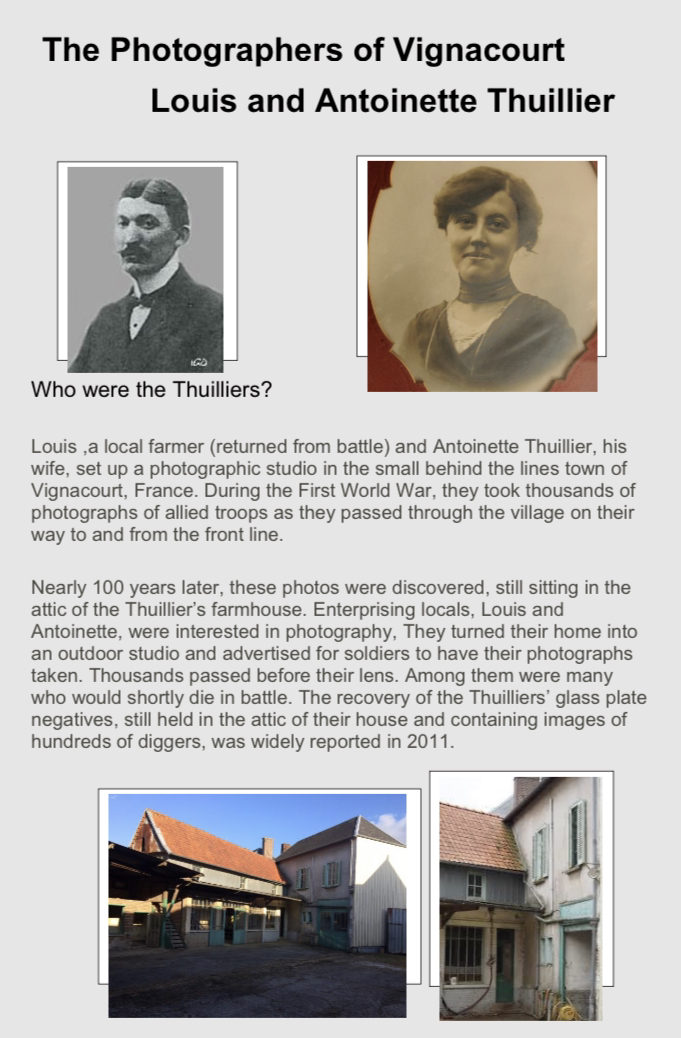

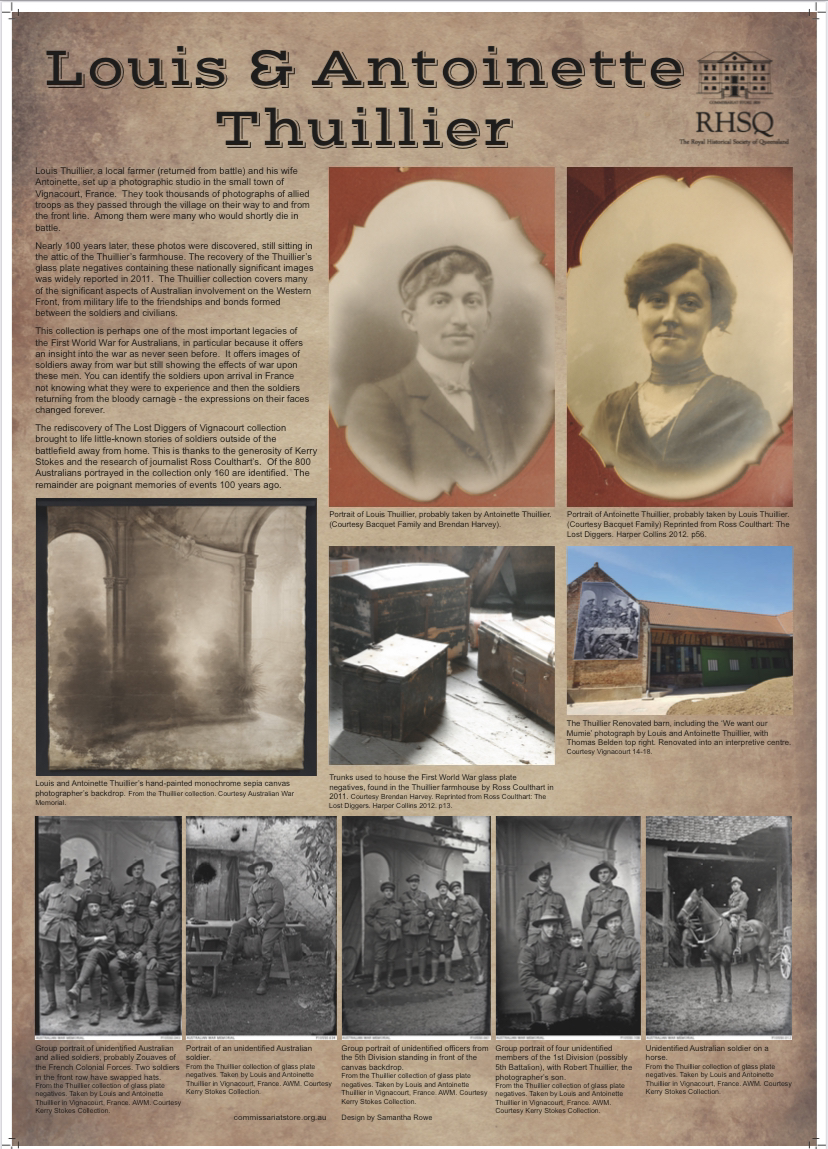

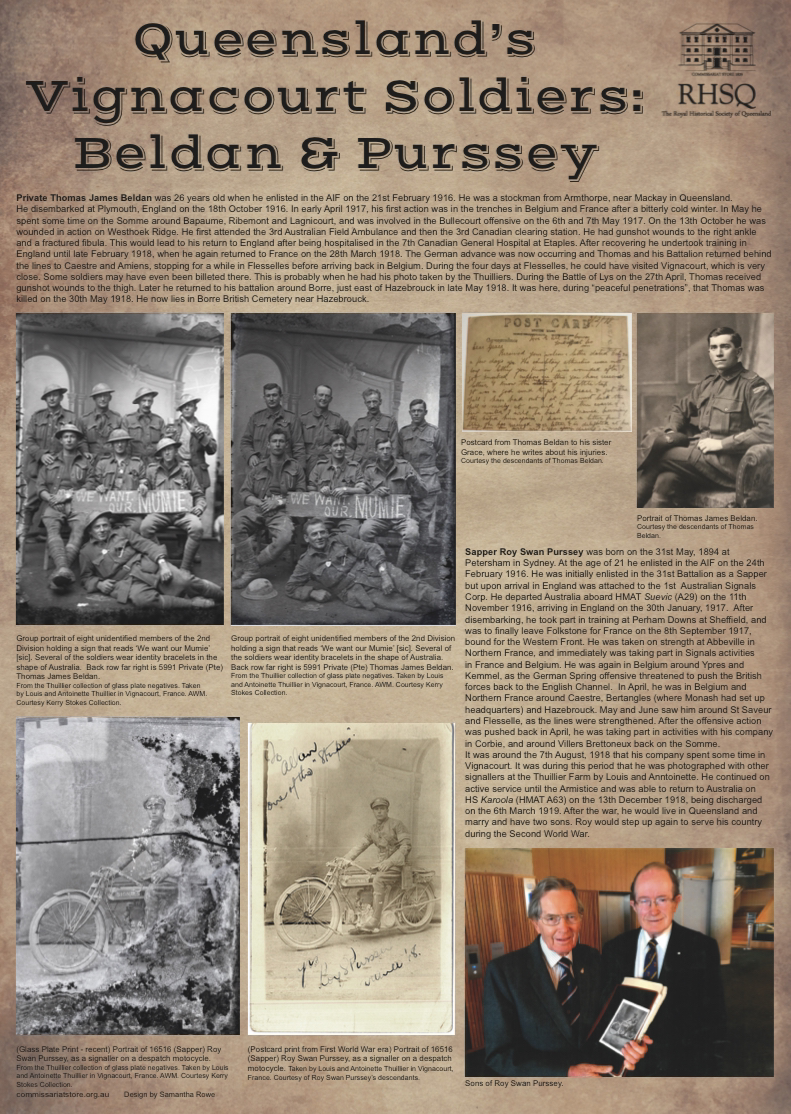

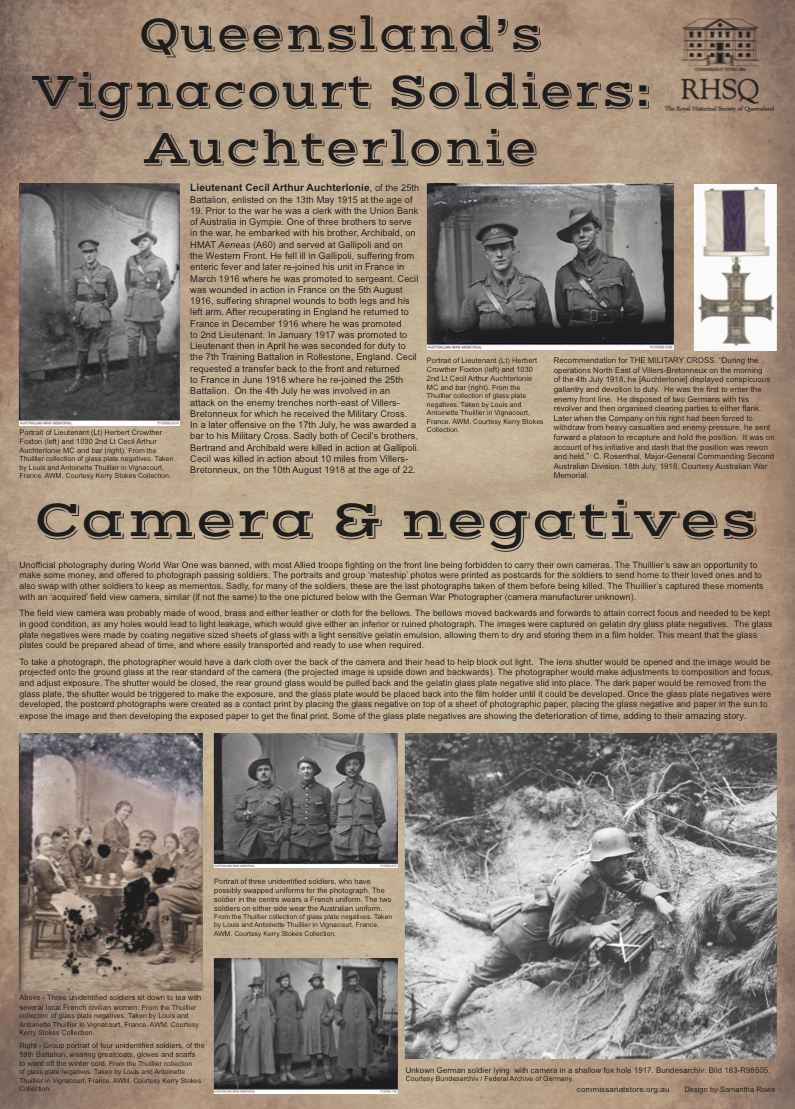

Vignacourt is the story of how one enterprising photographer took the opportunity of this passing traffic to establish a business taking portrait photographs.

Captured on glass, printed into postcards and posted home, the photographs made by the Thuillier family enabled Australian and other soldiers to maintain a fragile link with loved ones at home.

Courtesy Peter Burness AWM

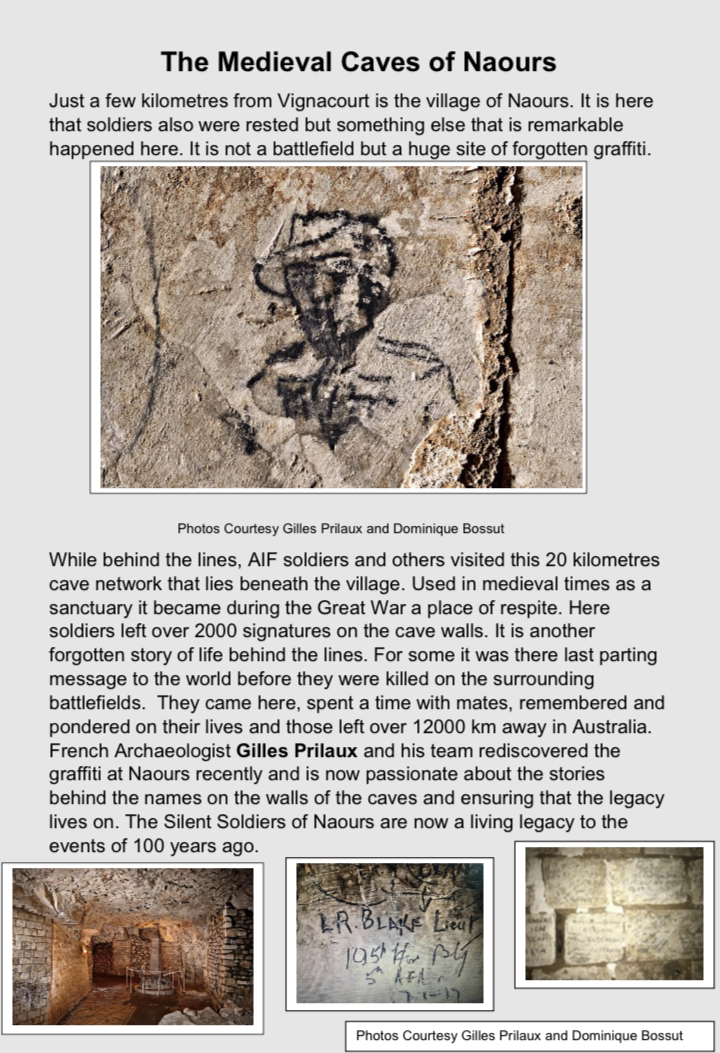

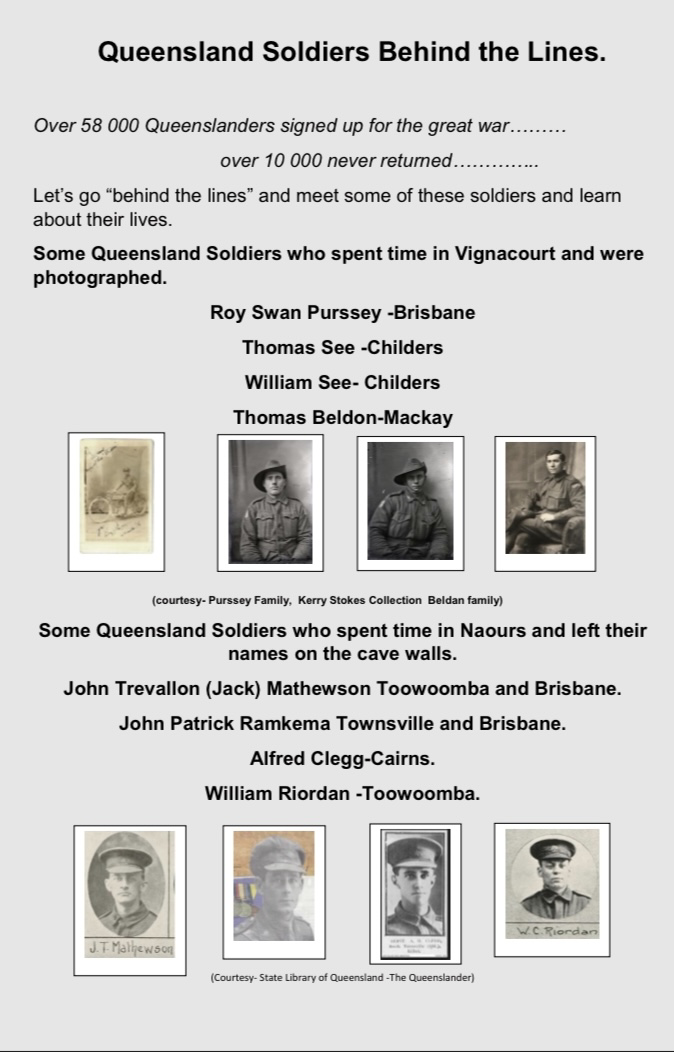

Naours

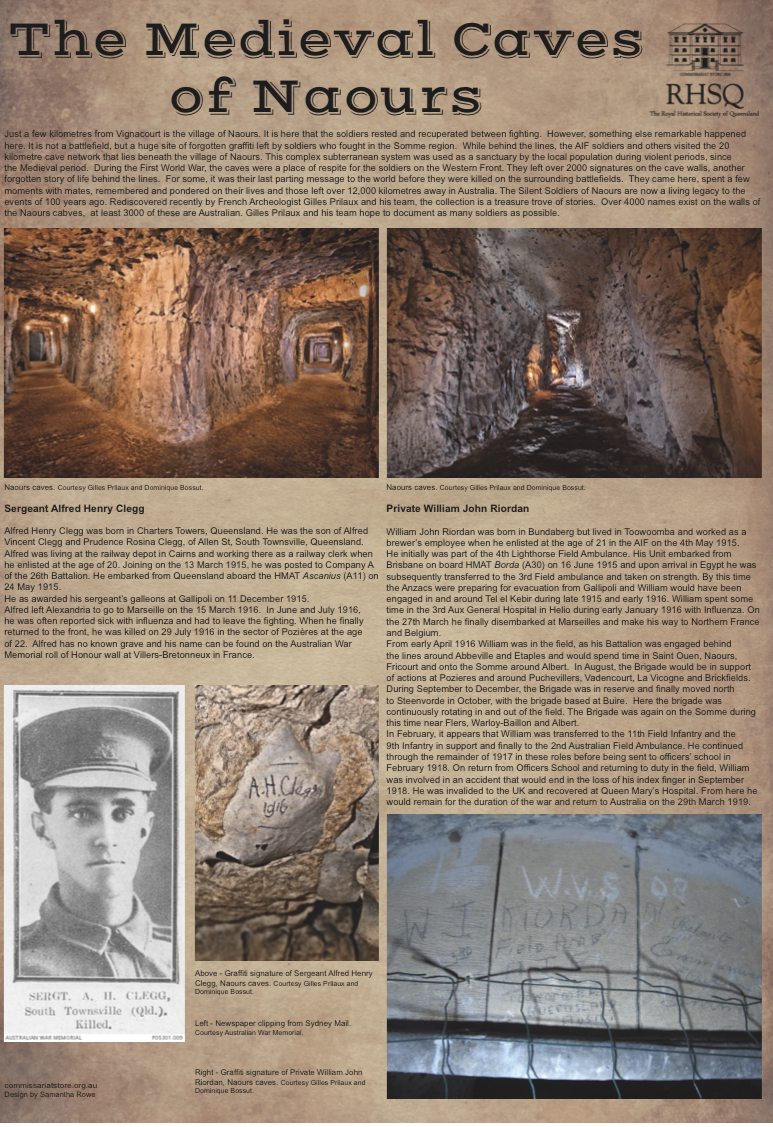

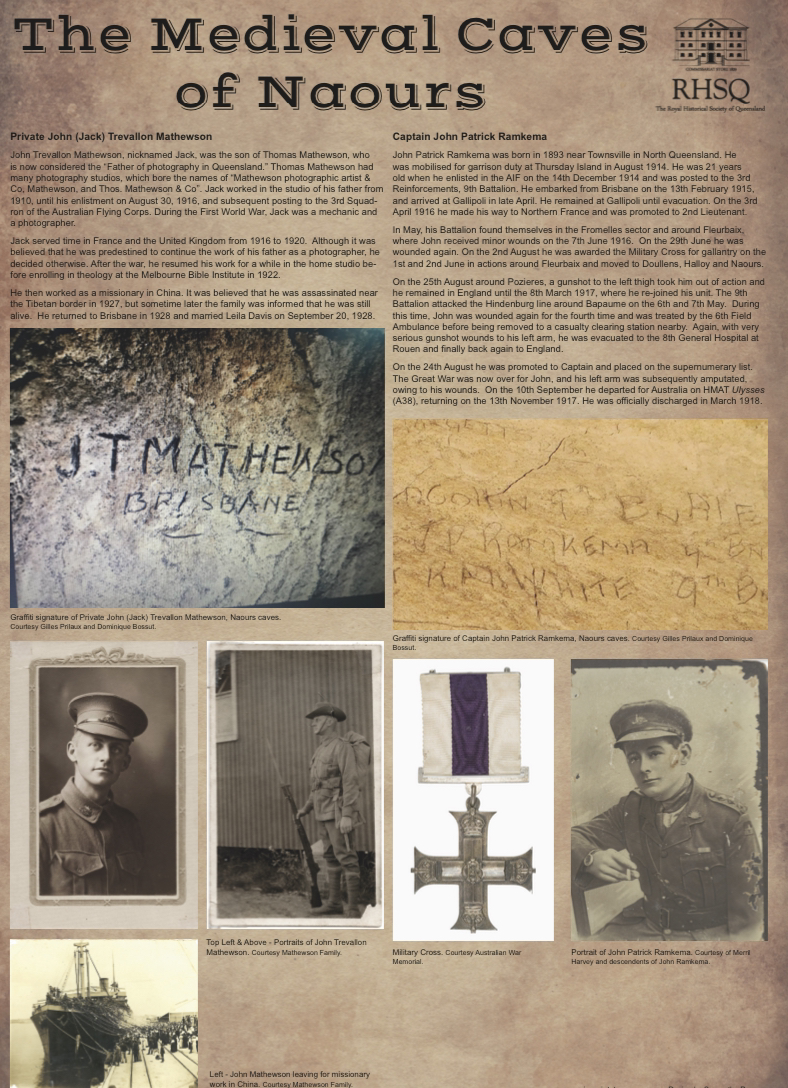

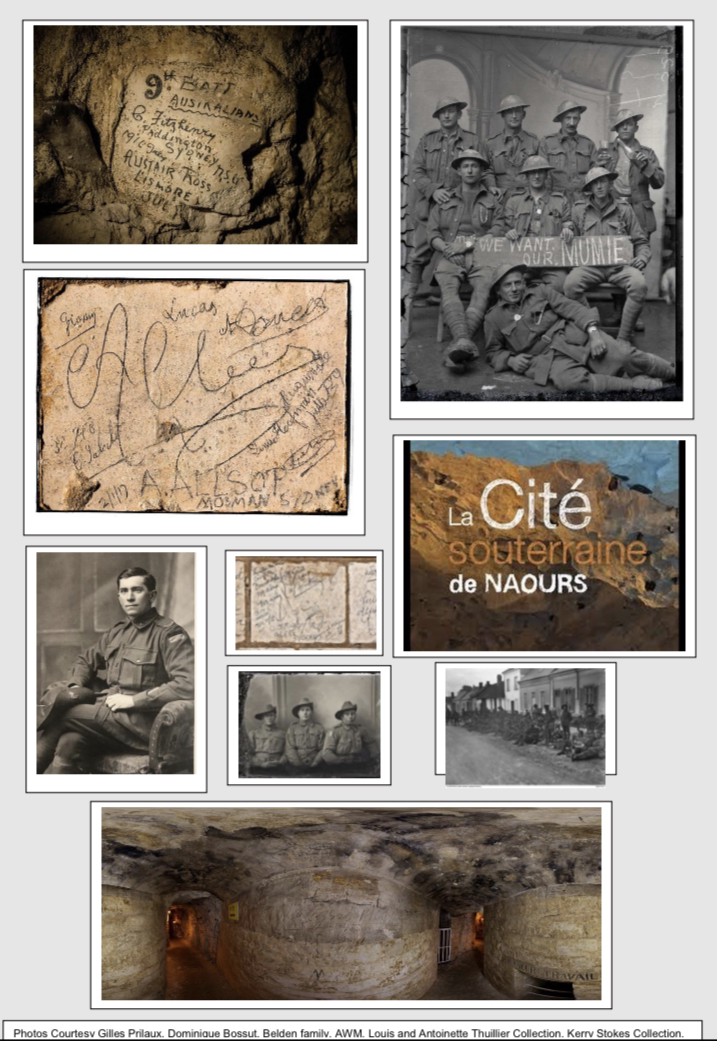

The underground portion of Naours began as a quarry in antiquity that was steadily enlarged over successive centuries. The empty subterranean chambers gave area residents a convenient place to store goods and take shelter from the elements, and to hide from raiders and roving armies looking for supplies. By the 17th century, thanks to the rampant destruction of the Thirty Years’ War, the underground city had a large and fairly well-settled contingent of residents.Consisting of 300 rooms and 28 galleries, the Cité souterraine de Naours hosted roughly 3000 people at its height. Along with these human inhabitants, there were also spaces for keeping livestock, as well as three chapels, multiple town squares, and a bakery with working ovens. The chimneys from these ovens and from any other fires underground were carefully routed through the existing structures aboveground to hide the existence of the daily life taking place 22 meters (72 feet) below ground.

As Western Europe stabilized and hiding in caves for long periods of time became less necessary, the existence of this underground complex was forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1887. True to its past form, the hidden network of chambers was a popular sightseeing attraction among World War I soldiers on the Western front as well as a billeting village

located well behind the lines for soldiers from many lands. Today it boasts the highest concentration of graffiti from the Great War. It was also used as a headquarters by occupying Nazi forces in World War II. The Cité souterraine de Naours is today one of the largest tunnel networks in northern France.

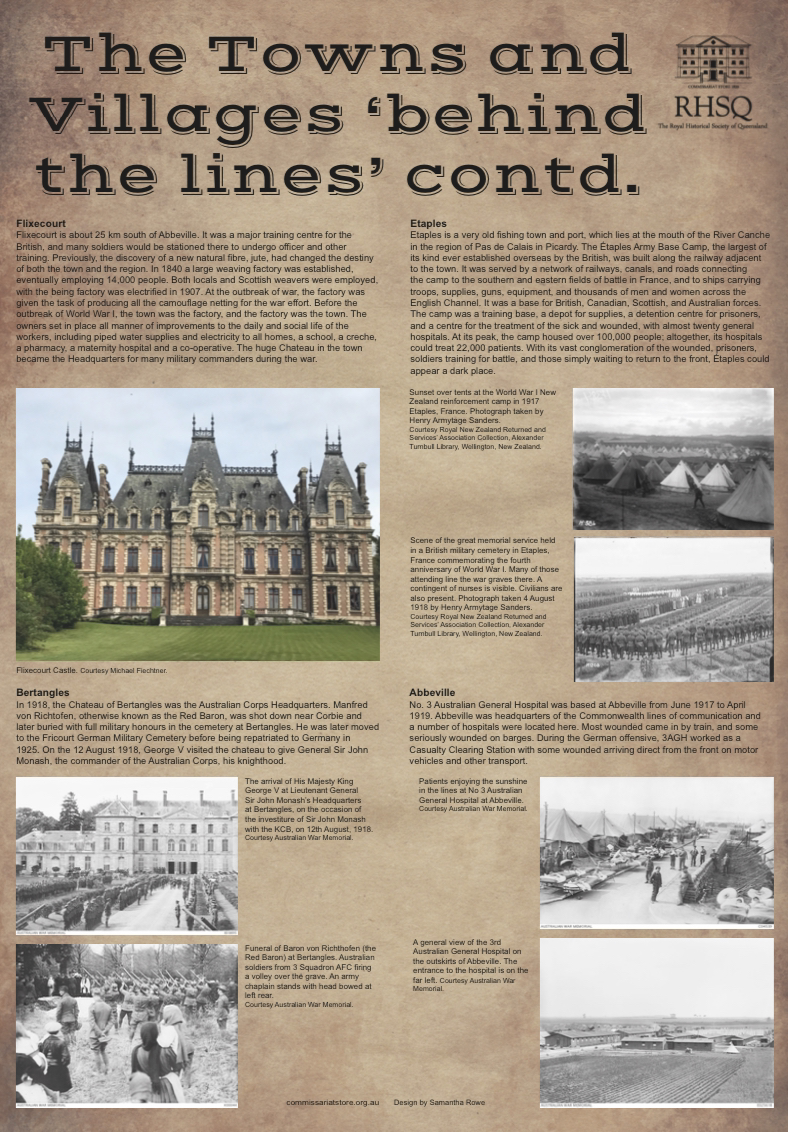

Bertangles

In 1918, the Chateau of Bertangles was the Australian Corps Headquarters. Manfred von Richtofen, otherwise known as the Red Baron, was shot down near Corbie and later buried with full military honours in the cemetery at Bertangles. He was later moved to the Fricourt German Military Cemetery before being repatriated to Germany in 1925. On the 12 August 1918, George V visited the chateau to give General Sir John Monash, the commander of the Australian Corps, his knighthood.

Abbeville

No. 3 Australian General Hospital was based at Abbeville from June 1917 to April 1919. Abbeville was headquarters of the Commonwealth lines of communication and a number of hospitals were located here. Most wounded came in by train, some seriously wounded on barges. During the German offensive, 3AGH worked as a Casualty Clearing Station with some wounded arriving direct from the front on motor vehicles and other transport.

Étaples

Étaples is a very old fishing town and port, which lies at the mouth of the River Canche in the region of Pas de Calais in Picardy. The Étaples Army Base Camp, the largest of its kind ever established overseas by the British, was built along the railway adjacent to the town. It was served by a network of railways, canals, and roads connecting the camp to the southern and eastern fields of battle in France and to ships carrying troops, supplies, guns, equipment, and thousands of men and women across the English Channel. It was a base for British, Canadian, Scottish and Australian forces.

The camp was a training base, a depot for supplies, a detention centre for prisoners and a centre for the treatment of the sick and wounded, with almost twenty general hospitals. At its peak, the camp housed over 100,000 people; altogether, its hospitals could treat 22,000 patients.

With its vast conglomeration of the wounded, of prisoners, of soldiers training for battle and of those simply waiting to return to the front, Étaples could appear a dark place.

Flixecourt

Flixecourt is about 25 km south of Abbeville. It was a major training centre for the British and many soldiers would be stationed there to undergo officer and other training. The discovery of a new natural fibre, jute changed the destiny of both the town and the region. Large weaving factories had been established there before the war and with the outbreak of war were given the task of producing all the camouflage netting for the great war. Locals and Scottish weavers were employed. The factory was electrified in 1907. Before the outbreak of World War I, 14,000 people were employed here. The town was the factory, and the factory was the town. The owners set in place all manner of improvements to the daily and social life of the workers. Piped water supplies and electricity to all homes, a school, a creche, a pharmacy, a maternity hospital and a co-operative. The huge chateau in the town became the Headquarters for many military commanders during the war.

Vignacourt was distant enough from the fighting to be beyond artillery range but close enough to be an important billeting place,rail centre, base, and training area for troops within what became the British sector of the front. Its importance would ebb and flow, depending on the closeness of the fighting. At various times it also held headquarters, a signals centre and hospitals, and for a while an airfield operated on its outskirts. For many troops Vignacourt was a refuge. Many remembered it as a place where they recovered from heavy battle and prepared for the next. During the war thousands were billeted in houses or slept in the local barns, stables and lofts. The surrounding fields were alive with training grounds and camps. Evenings were often free, with the chance for troops to visit the cafes and estaminets, which filled with rowdy banter and merry laughter over plates of eggs and chips and glasses of beer or wine.

Photo Naours 1916 courtesy AWM

For a couple of months in late 1916 and again in 1918, hundreds of Australians struggled down from the Somme winter trenches to Vignacourt. Here baths and laundries were set up and army stores issued fresh clothing. Most important of all, there were homes with women, children and even pets. It was a rare glimpse of the domestic life they had left behind. Young Frenchmen were noticeably few, as most were away serving in the army. Still there were always some around, mostly soldiers on leave visiting their families.

Vignacourt is the story of how one enterprising photographer took the opportunity of this passing traffic to establish a business taking portrait photographs.

Captured on glass, printed into postcards and posted home, the photographs made by the Thuillier family enabled Australian and other soldiers to maintain a fragile link with loved ones at home.

Courtesy Peter Burness AWM

Naours

The underground portion of Naours began as a quarry in antiquity that was steadily enlarged over successive centuries. The empty subterranean chambers gave area residents a convenient place to store goods and take shelter from the elements, and to hide from raiders and roving armies looking for supplies. By the 17th century, thanks to the rampant destruction of the Thirty Years’ War, the underground city had a large and fairly well-settled contingent of residents.Consisting of 300 rooms and 28 galleries, the Cité souterraine de Naours hosted roughly 3000 people at its height. Along with these human inhabitants, there were also spaces for keeping livestock, as well as three chapels, multiple town squares, and a bakery with working ovens. The chimneys from these ovens and from any other fires underground were carefully routed through the existing structures aboveground to hide the existence of the daily life taking place 22 meters (72 feet) below ground.

As Western Europe stabilized and hiding in caves for long periods of time became less necessary, the existence of this underground complex was forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1887. True to its past form, the hidden network of chambers was a popular sightseeing attraction among World War I soldiers on the Western front as well as a billeting village

located well behind the lines for soldiers from many lands. Today it boasts the highest concentration of graffiti from the Great War. It was also used as a headquarters by occupying Nazi forces in World War II. The Cité souterraine de Naours is today one of the largest tunnel networks in northern France.

Bertangles

In 1918, the Chateau of Bertangles was the Australian Corps Headquarters. Manfred von Richtofen, otherwise known as the Red Baron, was shot down near Corbie and later buried with full military honours in the cemetery at Bertangles. He was later moved to the Fricourt German Military Cemetery before being repatriated to Germany in 1925. On the 12 August 1918, George V visited the chateau to give General Sir John Monash, the commander of the Australian Corps, his knighthood.

Abbeville

No. 3 Australian General Hospital was based at Abbeville from June 1917 to April 1919. Abbeville was headquarters of the Commonwealth lines of communication and a number of hospitals were located here. Most wounded came in by train, some seriously wounded on barges. During the German offensive, 3AGH worked as a Casualty Clearing Station with some wounded arriving direct from the front on motor vehicles and other transport.

Étaples

Étaples is a very old fishing town and port, which lies at the mouth of the River Canche in the region of Pas de Calais in Picardy. The Étaples Army Base Camp, the largest of its kind ever established overseas by the British, was built along the railway adjacent to the town. It was served by a network of railways, canals, and roads connecting the camp to the southern and eastern fields of battle in France and to ships carrying troops, supplies, guns, equipment, and thousands of men and women across the English Channel. It was a base for British, Canadian, Scottish and Australian forces.

The camp was a training base, a depot for supplies, a detention centre for prisoners and a centre for the treatment of the sick and wounded, with almost twenty general hospitals. At its peak, the camp housed over 100,000 people; altogether, its hospitals could treat 22,000 patients.

With its vast conglomeration of the wounded, of prisoners, of soldiers training for battle and of those simply waiting to return to the front, Étaples could appear a dark place.

Flixecourt

Flixecourt is about 25 km south of Abbeville. It was a major training centre for the British and many soldiers would be stationed there to undergo officer and other training. The discovery of a new natural fibre, jute changed the destiny of both the town and the region. Large weaving factories had been established there before the war and with the outbreak of war were given the task of producing all the camouflage netting for the great war. Locals and Scottish weavers were employed. The factory was electrified in 1907. Before the outbreak of World War I, 14,000 people were employed here. The town was the factory, and the factory was the town. The owners set in place all manner of improvements to the daily and social life of the workers. Piped water supplies and electricity to all homes, a school, a creche, a pharmacy, a maternity hospital and a co-operative. The huge chateau in the town became the Headquarters for many military commanders during the war.